Article by Professor Paul McGreevy, BVSc, PhD, FRCVS

This article will help all horse owners who are either grappling with an end-of-life decision or aiming to plan ahead. It covers when and how to take the decision and who to involve. It explains the difference between welfare state and quality-of-life, and how to assess them. It discusses practical considerations of caring for chronically ill or senior horses, and will touch on some of the ethical and moral dimensions that affect our decision-making.

It complements this Horses and People article by Dr Andrea Harvey that discusses, in great detail, the end-of-life options for horses, exploring the advantages and disadvantages of these options as well as the problems with horse slaughter.

The hardest decision by far

We love our horses. They enrich our lives in countless ways. The amount of time, emotional energy and financial resources we spend on them all reflect the appreciative regard in which we hold each and every one of them.

However, the privilege of owning and caring for such magnificent creatures comes with a responsibility for making hard decisions on their behalf. And of these, the hardest we will ever make is when to end their life.

It’s a distressing choice we make to avoid putting our horse through more suffering than is necessary. It’s our duty to do the right thing at the right time for our horse.

But how do we know the time has come?

We don’t want to euthanase horses too early, and we don’t want to euthanase too late. Deciding when to end a horse’s life is tough because it is complex and emotionally charged. Horse owners deserve to be understood and never judged as they grapple with multiple decisions; knowing when it’s time, how to plan and who to involve.

A helpful first step, before we unpack the horse welfare and quality-of-life aspects of the decision-making process, is to reflect on your values:

- Do you believe in euthanasia?

- Do you value quality-of-life over quantity-of-life?

- Which is more important to you, extending the horse’s life, or providing him or her with a controlled death?

- Would you keep your horse alive despite declining quality of life because you’d rather not confront the decision to euthanase?

- Do you accept that, perhaps in the light of discussions with others, you might change your mind when the time comes?

It is worth taking time to ponder these questions because even when, in principle, you agree with euthanasia and you want to do the right thing for your horse, recognising the time has come and being able to act can still present challenges, and delay the decision.

Indeed, the statistics tell us that in most cases, the decision to euthanase a horse is more vulnerable to an excessive delay than an unseemly rush. And yet, the last thing a caring horse owner wants to deal with is the prospect, real or imagined, that they left the decision too late.

How and why do we put off these decisions?

The notion that “where there is life there is hope” is often bandied around by those struggling to take a decision of this sort. Veterinarians encounter many stalling points such as “now is not a good time just ahead of Christmas” or “our daughter’s wedding is next month”.

Even the time of year might affect decision-making. Because weight can fluctuate with the quality of grass and the environmental challenges of keeping warm, it is easy to imagine that current weight loss is only seasonal and will resolve when the seasons change.

For example, if a horse is struggling to maintain weight during Winter, one may be tempted to imagine that the warmer weather and the Spring grass may be all that is needed to help the horse turn the corner once more.

Some owners may talk themselves into keeping a mare for breeding purposes even though this is not in the horse’s best interests. Indeed, there are accounts of aged (and even laminitic) mares that have been kept alive, in slings, so that they can deliver their last foal.

Euthanasia may even be delayed because the ground is too tough or too boggy for an earthmover to be draughted-in at short notice for burial.

Other times, people put-off making a decision because it is difficult to reach consensus among many stakeholders and nobody wants to be the first person to raise or pursue the issue.

Who makes the call?

Taking the decision to euthanase a horse whose quality-of-life is declining is one of the kindest things we can do as veterinarians. That said, very few of us are taking the decisions regularly enough to consider ourselves experts.

In the light of recent announcements from veterinary associations in the UK and Australia about the expectation that vets will advocate for animals, vets must provide information that advances the welfare of animals in their care.

Although often consulted, veterinarians are trained to place responsibility for requesting euthanasia of their animals entirely with their clients. This means that the decision to euthanase will ultimately fall on those responsible for the horse’s care – owners who could be completely uninitiated in taking these decisions or be facing a complete moral conundrum.

We tend to assume that horses belong to one owner but, in reality, there are usually other key stakeholders who need to be identified and involved in end-of-life decisions and planning. Who they are, will depend on whether the horse in question is primarily perceived as a member of the family, a performance or production horse.

And there are many horses that do not fit neatly into just one of these three categories and bridge more than one. This will affect the way decisions are made and who is involved in reaching them. For example, a performance horse may very easily have won the hearts of all its carers and gained the status of a companion.

Here the role of attachment comes into play. The bond we develop with our horses can influence the time we take to reach end-of-life decisions and the extent to which we feel the need to consult others.

For example, a family pony, who is no longer ridden because the children who rode him have grown up and moved out, might be under the parents’ responsibility but still retains a place in the hearts of all the family members. In this situation, the need to consult the children should not be overlooked in the planning process.

Support and counseling

If you’re uncomfortable with your decision-making, identify two or three different people who share your values and know your horse, and then runyour thinking past them. It is critical that you avoid inadvertently selecting these informal advisors primarily on the basis that they will be likely to agree with you.

Indeed, your general horse care plan should include nominating at least one person who can make decisions on behalf of your horse should you be incapacitated through illness or an accident.

Who will you involve?

Your end-of-life plan should also include a consideration of who will be present when euthanasia takes place.

Consider the visual memories you want to keep of your beloved horse and be kind to yourself when deciding whether you want to be present at the time of death and/or burial.

What about the other horses?

There is also merit in planning what to do with the other horses at the time of death and burial. These aspects can create additional stalling points especially because there is so little peer-reviewed research in this domain.

Towing the body (for example, to a grave or truck) or dropping the horse in front of others is not recommended because such a visual stimulus is unlikely to be familiar and could cause fear in the other horses. But allowing horses to visit the remains of a companion may potentially help them to deal with the absence of familiar herd-mates.

Everyone who has been around horses long enough has an anecdote about how horses respond to the death of others in their social group.

For example, there are reports of mares whose foal died, standing with the corpse for a time and then losing interest. These accounts are used to guide decisions about whether horses should be allowed to inspect the remains of their companions.

Of course, the plural of anecdote is data. We urgently need research that collates these anecdotes and makes sense of them. In the absence of research, it seems to make sense that horses can benefit from investigating a horse on the ground.

Other considerations

It is worth considering the value of collecting a memento, such as tail hair that can be made into a special keepsake or, well ahead of the day of euthanasia, organising a professional photo shoot to capture a beautiful lasting memory.

At times of significant grief, such measures can be overlooked unless one builds an informal checklist of actions that need to be undertaken either before, at the time of death or shortly after. Veterinarians and their staff should encourage owners to think about the memories they want to keep in advance.

It is also possible that, with the anticipated introduction of a national horse traceability register, owners will be required to report the death of any horse registered with them within a set period.

A detailed discussion of the methods of euthanasia can be found in this article by Dr Andrea Harvey

Confronting chronic illness

The medical and practical considerations that influence your approach to horse care, particularly in the context of chronic and/or age-related illness, should be openly discussed with all stakeholders.

-

Medical considerations

A chronic disease in senior horses can compromise their quality-of-life, but for the owners who spend time with their horses every day, it is sometimes easy to mistake clinical signs of disease as normal signs of ageing. This is why it is well worth asking your vet for help.

- Ask your veterinarian to assess your horse’s condition, to establish if he or she is suffering, and if that can be alleviated with pain relief, medicine, surgery or other treatment.

- Consider the likely outcome of treatment (prognosis).

- Ask your veterinarian to explain clearly which behaviours they see as critical to identify any decline, and when the thresholds of acceptability have been crossed – then be prepared to monitor these metrics closely in your horse. After all, you are the person who knows your horse best.

- Communicate faithfully to your family (or other stakeholders) what your veterinarian has advised.

-

Practical considerations

Think about the practicalities of caring for your horse as he or she approaches terminal illness or infirmity.

- Establish whether your horse is going to suffer without treatment and how you would know.

- Consider whether there will always be someone to provide adequate monitoring.

- Ask yourself if you can attend and support vet visits and administer regular medication.

- Assess the anticipated burden of increased responsibility and associated stress, and evaluate whether you and your family can manage it.

Appreciating these realities and confronting them as a preliminary part of the decision to euthanase, can help us put our grief to one side for a moment and ensure that we act only in the interests of the animal, not ourselves.

A detailed discussion of the methods of euthanasia can be found in this article by Dr Andrea Harvey

Welfare state and quality-of-life

The animal’s welfare is often captured in the term quality-of-life, the key distinction between the terms is that quality-of-life is evaluated over time.

At any single moment, a horse can have good or bad welfare but their quality-of-life is a function of their welfare across an extended period. In this way, one can think of quality-of-life as being synonymous with the ‘animal’s welfare over time’.

An arthritic horse, for example, could indulge in play in the morning and then pay the price; showing marked pain-related behaviour in the afternoon. This means he may have good welfare at 11am and poor welfare at 4pm, but his quality-of-life depends on the overall combination of experiences during the whole day.

With this in mind, the most sensible approach to determining quality-of-life is to take regular welfare assessments over a period of days or weeks.

Quality-of-life assessments

For dogs, there are several quality-of-life assessment tools that can help owners make end-of-life decisions. Some of these require owners and carers to rate behaviours, such as mobility, on a scale from 1 to 10. Other quality-of-life assessment tools prompt owners to weigh-up the pleasant and unpleasant experiences the animal is exposed to.

Once they have been developed and validated, quality-of-life assessments for horses will be helpful for guiding discussions with family and vets. Bear in mind that validating any assessment tools for companion animals is complex, because of differences between individuals and their circumstances, and because we can never truly know what another animal (or human) experiences.

Even if validated quality-of-life assessment tools for horses do become available, they will never be absolute and must still be used over time to reveal trends that elevate decision-making above a mere snapshot. Observing a gradual decline is more informative than noting that the horse has been having a bad day.

As an exercise in distancing oneself from the direct personal effects that tough decisions can have, it may pay to consider the horse’s welfare from the perspective of a concerned, experienced neighbour.

This may mean imagining what a notional horse vet next door might think every time she drives past the paddock and makes a cursory assessment of the horse’s demeanour and behaviour.

How many assessments are needed?

Like all of us, horses have good days and bad days, and this oscillation in apparent wellbeing means that we very rarely make well-informed decisions in relative isolation or on the spot.

And like all animals, horses can have an overwhelming instinct for survival. So, at times, it can be difficult to differentiate between them going through a bad patch or entering a terminal decline.

As carers, it is our responsibility to ensure that we recognise when the bad days are becoming more frequent and the good days are becoming more scarce. And to resist becoming habituated to the appearance of a horse whose health and wellbeing are slowly declining.

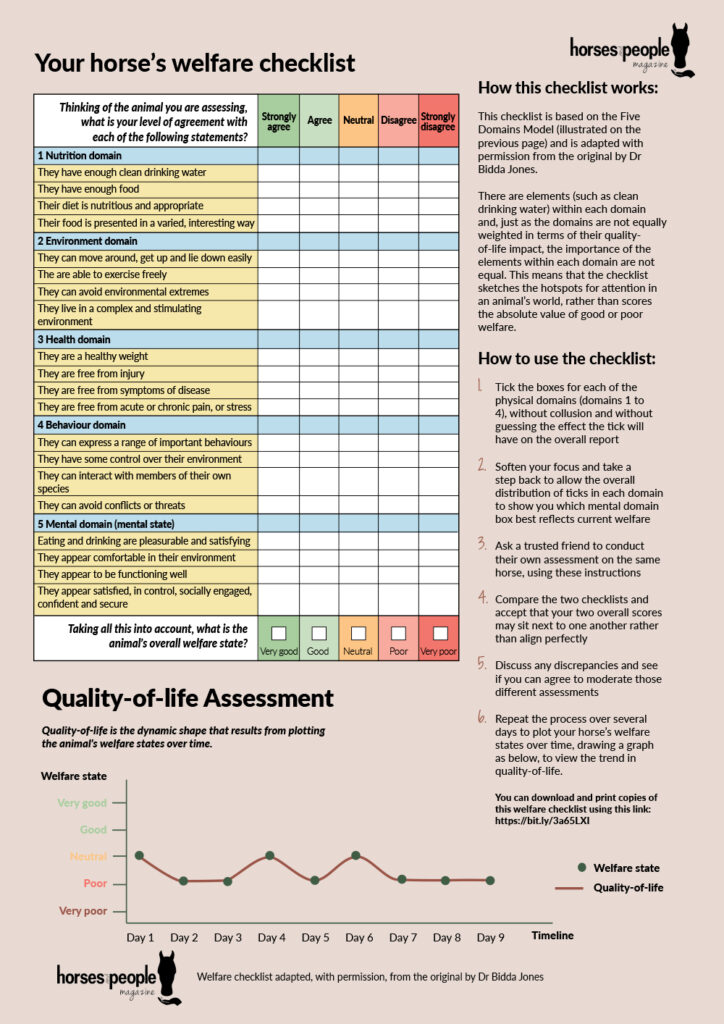

Recording objective data that can be used to work out when the balance of the good and bad is shifting, is strongly recommended. This can be as simple as keeping notes on your smartphone, or a more detailed checklist as shown here.

Maintaining such records is one thing but knowing what to do with information before the heat is on is absolutely critical.

The sort of data one keeps will depend on the framework you use to judge your horse’s welfare.

Choosing a Quality-of-Life framework

The decision will ultimately fall on you – the carer – and this can be a good thing because after all, you have more day-to-day information about the animals’ interactions with his/her environment, including other horses and animals.

The key is to ensure that we use this information to act in the animals’ best interests. We must do all that we can to avoid making decisions to suit our needs rather than those of the animals. This usually means having to collect cold, hard data that can inform our decisions.

For example, you could note how often a senior horse stumbles while trying to keep up with others in the paddock. This may require observing them directly for 10 minutes or so on a regular basis to record any meaningful decline in their ability to move around.

Musculoskeletal injuries can affect a horse’s ability to lie down and, afterwards, get to their feet again. This means that affected horses are less likely to sleep on the ground.

This may, at first glance, appear to be inconsequential because horses can sleep standing up. However, not all types of sleep are as valuable as each other. Lack of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, that horses are thought to undertake only when lying on the ground, is likely to compromise welfare.

So, monitoring what your horse is doing during the 24-hour day can be an invaluable tool in welfare assessment. Wearable devices to track and monitor your horse’s activity and temperature are likely to become more readily available and become tools that will contribute to welfare assessment.

The Five Domains framework

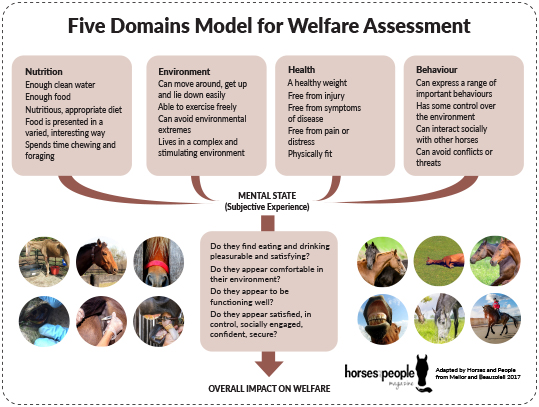

An everyday framework for planning end-of-life decisions uses the Five Domains model that was developed by Emeritus Professor David Mellor and his team at Massey University, and has been updated over time according to emerging behavioural, physiological and neuroscientific evidence.

The Five Domains model has been considered by veterinary practitioners and welfare scientists for several years now and has been used in workshops to test its flexibility and utility for assessing horse welfare in the field.

It has been adapted to provide a practical means of assessing negative or adverse welfare impacts on animals in several different areas, initially to assess the impact of vertebrate pest control methods.

The model was first proposed as a means of evaluating the welfare impact of interventions on horses by Jones and McGreevy in 2010, and details of its use in everyday horse-keeping activities have been published online.

The welfare checklist we propose here (see below) is based on this model and explores welfare assessment under four topic headings (called domains) that reflect the horse’s nutrition, environment, behaviour and health.

There are outward signs that reflect these domains, for example, evidence of reduced appetite and pain. These signs are critical points from which to draw data but should be factored into end-of-life decisions.

You can see that one of the domains is health, an area that your vet is expert in. In contrast, the other physical domains – behaviour, nutrition and environment – that, along with health, feed into the fifth (mental) domain, rely on input from your own observations.

Below you will also find two made-up scenarios that show how a checklist, based on the Five Domains model, can be used to reveal quality-of-life trends.

While the Five Domains model was initially used to raise alarm bells about poor welfare, the current versions of the model have the benefit of including positive and negative welfare states. In the context of end-of-life decisions, it is critical that we assemble evidence of both types of welfare outcome.

Of course, we cannot apply scores very easily to each of the four physical domains and we must, therefore, be careful not to assume that each domain is as impactful on quality-of-life as the next.

The importance of each element is not equally weighted. However, many welfare scientists agree that behaviour is the key domain of interest to owners.

Graphing the data over time allows you to appreciate trends and assess them against the threshold of acceptable quality-of-life that you and other carers have agreed upon in your planning.

There is a clear need for more science to clarify the relative importance of each domain and each element within it. Nevertheless, the beauty of this framework is that it allows structured discussion between stakeholders.

Last thoughts

The unquestionable value of planning end-of-life decisions for your animals lies chiefly in its ability to avoid extended suffering.

Time and time again, the tough decisions are delayed because nobody wants to be perceived as too keen to see the departure of a valued individual animal lest they attract the label of the ‘hanging judge’. It is, therefore, very important that no single person should be asked to make a decision on behalf of others.

Even when only one owner or carer is involved, applying a framework such as the Five Domains model presented here has merit. If anything, it can lead a structured exploration of the key issues for each horse and the metrics that can be adopted to monitor quality-of-life progress or decline.

Ultimately, if and when you euthanase your horse is a deeply personal choice. That said, a comfortable death — either natural or assisted — is the last kindness you can offer them. By the same token, forward planning your horses’ end-of-life is a kindness to yourself.

A detailed discussion of the methods of euthanasia can be found in this article by Dr Andrea Harvey

Some examples showing the use of the welfare checklist: